Creative Portfolio

creative writing, long-form journalism, textual and visual archive of the matters of the heart, analog photography, essays

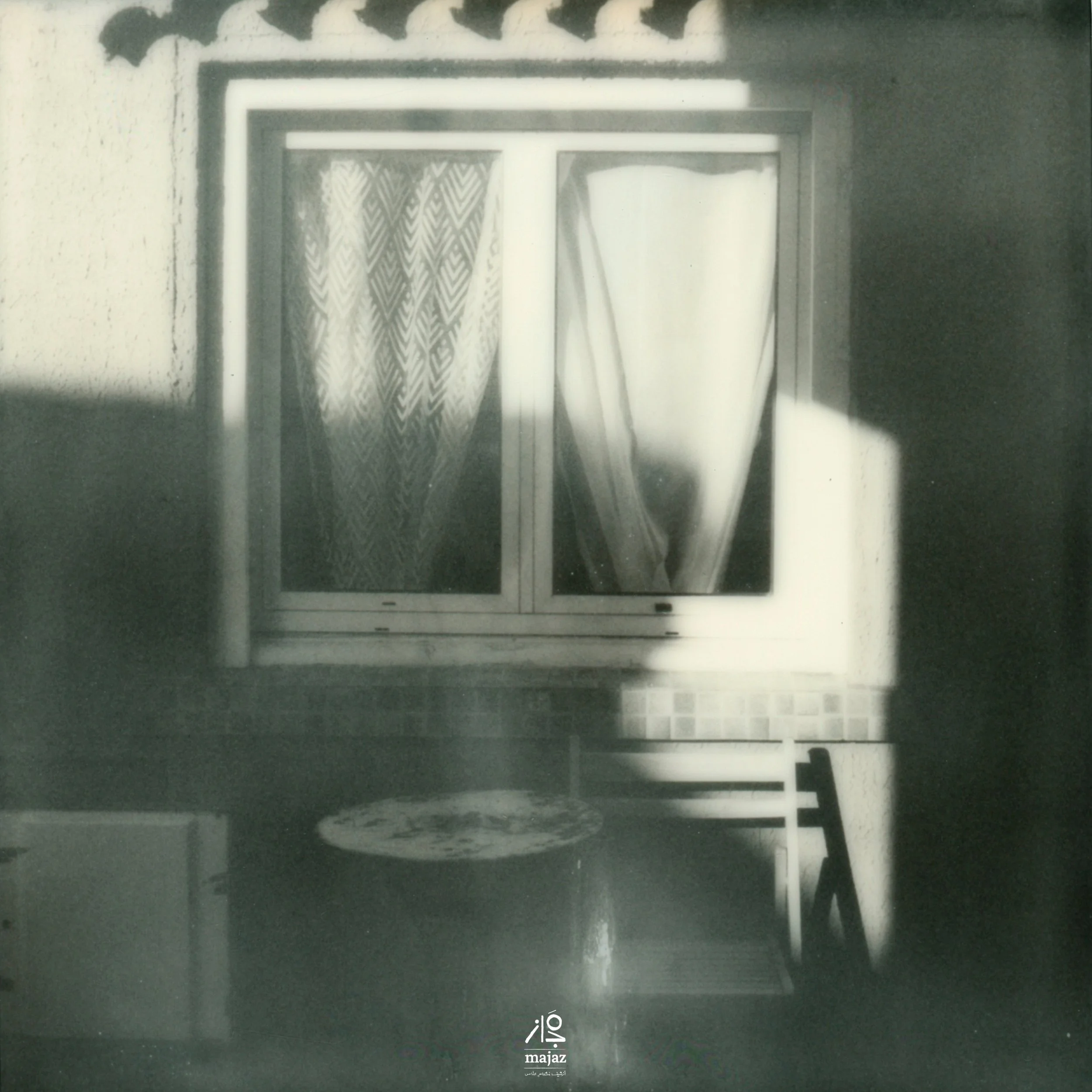

Founded in 2022, Majaz is a a digital magazine dedicated to slow, narrative long-form journalism and instant photography.

Majaz Magazine

In Arabic, Majaz means transcendence and passage. It also refers to a corridor or threshold. In architecture, Majaz describes the vestibule in an Arabic house—the passageway connecting the entrance to the central courtyard. This transitional space allows movement between private and public life while preserving the household’s privacy, ensuring that the shift from the communal to the intimate is subtle rather than abrupt.

Majaz serves as this transitional space within the Lebanese home—bridging the private and the public, the intimate and the communal, the individual and the collective. It seeks to open up conversations about the direct and indirect impact of political, social, and cultural issues on everyday life. At its core, Majaz treats journalism as a way to capture the rhythms of daily life and observe its smallest details.

Majaz magazine

Issue #01: The Absence of Longing for Elsewhere

When I asked a Lebanese friend why he had returned to settle in Lebanon after years in Europe, I anticipated a lengthy explanation. A list of reasons, perhaps even a manifesto. Instead, he said: "This is the only country where people are asked to explain why they're staying, not why they're leaving.”

At the time, I think I wanted him to frame his decision as an act of resistance—a commitment to the people he knew by name or at least by face, to a language he spoke without translation, or perhaps as his own small stand against the country's emptying out.

He dismissed the question, then pulled a new one from his pocket and handed it to me. I've kept it under my tongue ever since: What if people staying in their place was as natural and fluid as running water, not an act of resistance or cause for wonder?

My mother would always lament that her mother had never left her birthplace—not even for a brief visit beyond the Lebanese borders. She would say, with my aunt nodding in agreement, that my grandmother "never saw anything of this life." I felt sorry for my grandmother too, but over time I noticed my attention had shifted, as though it had migrated from the beginning of the sentence to its end. Instead of thinking about my grandmother, I found myself thinking about life.

How can life exist in one place and not in another? Or rather, how can life be everywhere, anywhere in the world, except in the place where we were born and where we live our days? What if, for my grandmother, life was the village—or even just the neighborhood?

I met Mira Minkarah on Wednesday, October 12, 2022, in Tripoli. We agreed to meet at "Warche 13" café in al-Mina. We talked for a full hour, if you count the many times we were interrupted by friends we ran into without appointments, or the times when the sound of a motorcycle engine drowned out our voices, or when we were stopped by a verbal altercation between a driver and stray dogs in the road. Afterward, we walked along the Mina corniche, where I took Polaroids of her and the sea.

I met Rana Eid on Wednesday, October 14, 2022 in Beirut. I met her at five in the afternoon at her private studio where she works as a sound designer for films and documentaries. I took an instant photo of her on the studio balcony before beginning the session, fearing that the sun would have set completely by the time our conversation ended, which is indeed what happened. We returned from the balcony with two pictures: a picture of her face, and another of the scene around her.

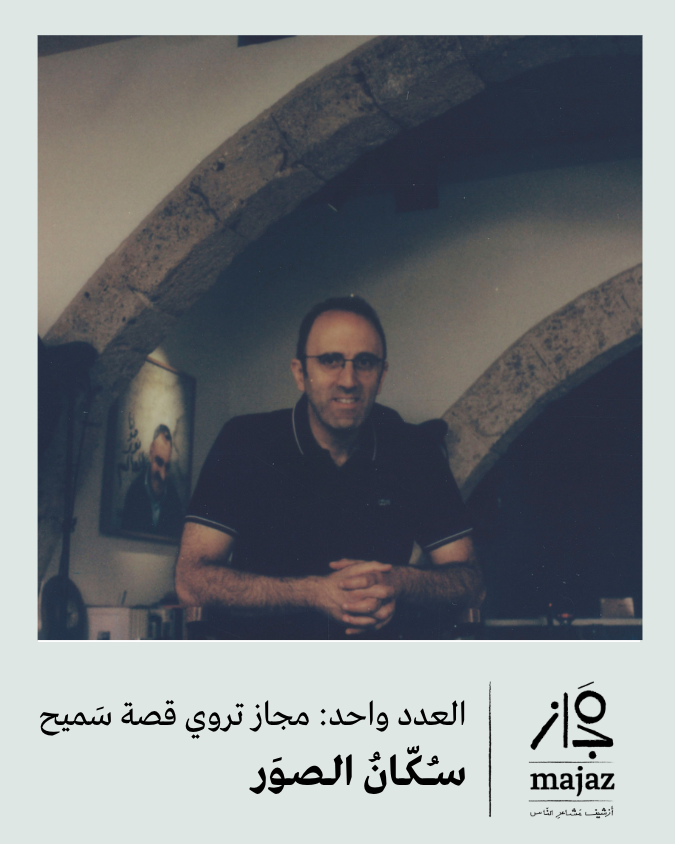

I met Samih Zaater on Thursday, October 13, 2022, in Zgharta. We agreed to meet at four in the afternoon at his studio in the Saydet el Gharbi neighborhood, the neighborhood where he's lived since he opened his eyes to the world. I left his studio about four hours later. Darkness had fallen. I visited him again on Friday morning, October 21, and took two Polaroids of him.

Majaz magazine

“I think I saw a dove!” Children Stories for Adults

"I Think I Saw a Dove" seeks to illuminate the present by examining the past. It treats the past as a bedside lamp in the room where the present rests. Each night, as the present tries to sleep, insomnia takes hold. A hand reaches for the lamp and switches it on. "Who Slaughtered the Dove?" becomes that lamp's glow, a small circle of light on the pillow, just enough to reveal the darkened rooms and hallways that exist within each of our minds during those sleepless hours.

This project explores these rooms and corridors of memory, excavating the past and bringing it into the present. It opens up essential conversations about childhood as a formative period in our lives, revealing how those early years continue to shape us as adults in both visible and hidden ways.

Majaz won a grant from the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) to produce this special issue.

Majaz Magazine

Collaboration with illustrator Lynn Jardali

In building an archive of human emotion, I wanted to create a glossary of feelings as they're actually lived, not clinical definitions, but intimate testimonies from real people. Each entry features someone from Majaz describing an emotion in their own words.

This poster captures loneliness through Souha's experience:

"One day, I felt such profound loneliness that I nearly lost my mind."

I envisioned this glossary as something tactile and physical—pages you could turn like archival documents or flip through like a collection of vinyl records. To bring these words into visual form, I collaborated with artist and illustrator Lynn, who helped transform raw emotion into something you can hold in your hands.

Sunday Afternoon Personal Blog

Think of this space as the bottom drawer of an old dresser in the house you grew up in, the drawer you’re only tempted to open on a Sunday after a long lunch. The table is cleared. Some people have left. Others are napping. Kids are bored. The cat that doesn’t live there but often visits is stretched in the sun. Dust sways in a thin ray of light. You sit on the floor, cross-legged, and you open the drawer.

Sunday Afternoon is a series of essays and reflections on life between places, cultures, and questions: part journalist’s eye, part writer’s notebook.

Inside: everything you never have time for. Fragments of the past. Notes you once scribbled and thought would be important. The tinted glasses you once wore to see the world, and suddenly, everything was pink. Dreams of who you wanted to become. And questions nested like Matryoshka dolls.

When you close it, the sun has set. You are still on the floor sitting like a child.

You are here.

It’s Sunday afternoon, and time is viscous, reluctant to flow.

SundayAfternoon

Is our first experience of America always a second-hand experience?

When my husband and I decided to move to the U.S., I had never set foot in any of the Americas. He’d already lived in Michigan for two years. For him, it was a return of sorts; for me, it was a new beginning. Or so I thought. As far as beginnings go, it felt like one. But the question that lodged itself in my mind had less to do with the noun than with the adjective: would anything here ever truly feel new in the United States of America?

Because in truth, I already “knew” America. I knew it because I wanted to: I’d watched the movies and series, sipped the occasional Starbucks iced latte—though I pride myself on preferring local artisan coffee wherever I’ve lived—and indulged in sugar-glazed donuts at Dunkin’ Donuts in Beirut. And I knew it because I had to: growing up in Lebanon meant learning the contours of American foreign policy long before the taste of an Americano. Put simply, I knew who Condoleezza Rice was years before I’d heard the words “pumpkin spice.”

Fiction

Tangerine

Her grandmother warned her not to fall into the trap. She didn’t say what it looked like, or when or how one might typically encounter it. She used the article “the,” not “a,” as if there was only one trap to fall into, and everyone must look out for it at all times.

She does not remember the exact sentence her grandmother used. In her head, it was a one-word sentence, although she is certain her grandmother couldn’t have uttered the word “trap” on its own. It must have been part of something like “beware of the trap,” but she can only recall the Arabic word her grandmother chose to use for “trap”: el-tahelké. A floating, singular word, like a tangerine hanging from the ceiling.

Published in ROOM:A Sketchbook for Analytic Action | 2.25